As the ongoing drought in Western states continues to worsen, agriculture is facing tough choices. In California, farmers are caught between climatological events and the decisions handed down by politicians and bureaucrats, and the end result in 2022-23 could have a permanent impact.

A story published Feb. 24 at https://www.morningagclips.com/citing-drought-us-wont-give-water-to-california-farmers/ noted that now in the third year of contending with severe drought, California’s Central Valley farmers have been told by federal officials that no water will be delivered for crops in the state’s primary ag region.

It was, the story said, “a decision that will force many to plant fewer crops in the fertile soil that yields the bulk of the nation’s fruits, nuts, and vegetables.”

Ernest Conant, regional director for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, said, “It’s devastating to the agricultural economy and to those people that rely on it. But unfortunately, we can’t make it rain.”

The story explained that the Central Valley Project in California, a complex system of dams, reservoirs, and canals is operated by the federal government and is one of two major water systems the state relies on for not only agriculture but also drinking water and the environment. The second system, the story said, is run by the state government.

The story also said that each year water agencies in California contract with the federal government for specific amounts of water, and in February the federal government announces “how much of those contracts can be fulfilled based on how much water is available.” Allocations are updated by the government throughout the year based on conditions.

In 2021 farmers started with a 5 percent allocation from the federal government but ended at 0 percent as the drought intensified, the story said. This year the starting point for farmers is 0 percent “while water for other purposes, including drinking and industrial uses, is at 25 percent.”

Conant was quoted as saying, “Last year was a very bad year. This year could turn out to be worse.”

The story cited Westlands Water District, which is the nation’s largest agricultural water district that encompasses 1,000 square miles square in Fresno and Kings counties, as saying that “drought conditions last year caused farmers to fallow 200,000 acres while leaving ‘thousands of acres of food unharvested.’”

Moreover, the district said it is the fourth time in a decade that farmers south of the San Joaquin-Sacramento River Delta have gotten no water from the federal government.

The state-run district is faring somewhat better with a 15 percent allocation made in January after December snowfall.

And, the story said, “State law requires both systems to have enough water available to maintain water quality throughout the San Joaquin-Sacramento River Delta, a sensitive environmental region home to endangered species of fish.”

Fish continue to die by the thousands, according to the story, because there hasn’t been enough cold water for them to survive,

The Westlands Water District said in a release earlier this year that it was “disappointed with the allocation but understood the drought and environmental laws ‘prevent Reclamation from making water available under the District’s contract.’”

As California moved farther into the third year of a severe drought and rain and snowfall remain well below historical averages, reservoirs in the Central Valley Project reservoirs were reported to be down in February by 26.5 percent compared to 2021.

“And through the end of September, federal officials predict the reservoirs will get 1.2 million acre-feet (1.4 billion cubic meters) less of water than they had planned. One acre-foot of water is typically enough to supply two average households for one year,” the story concluded.

To the east, Oregon and Idaho farmers are facing what’s been called the driest spell in more than 1,000 years, and the situation is expected to worsen.

A March 4 story published at https://www.ktvb.com/article/news/regional/scorched-earth/climatologists-drought-idaho-outlook-water/277-73120da1-3809-44ae-ba29-df063ae218d3 called the event a “22-year megadrought” and said in 2022 it deepened to the point that the “broader region is now in the driest spell in at least 1,200 years.”

It went on to say that climate scientists in the U.S. Pacific Northwest warned: “that much of Oregon and parts of Idaho can expect even tougher drought conditions this summer than in the previous two years, which already featured dwindling reservoirs, explosive wildfires, and deep cuts to agricultural irrigation.”

A news conference was hosted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, with water and climate experts from Oregon, Washington, and Idaho saying “parts of the region should prepare now for severe drought, wildfires and record-low stream flows that will hurt salmon and other fragile species.”

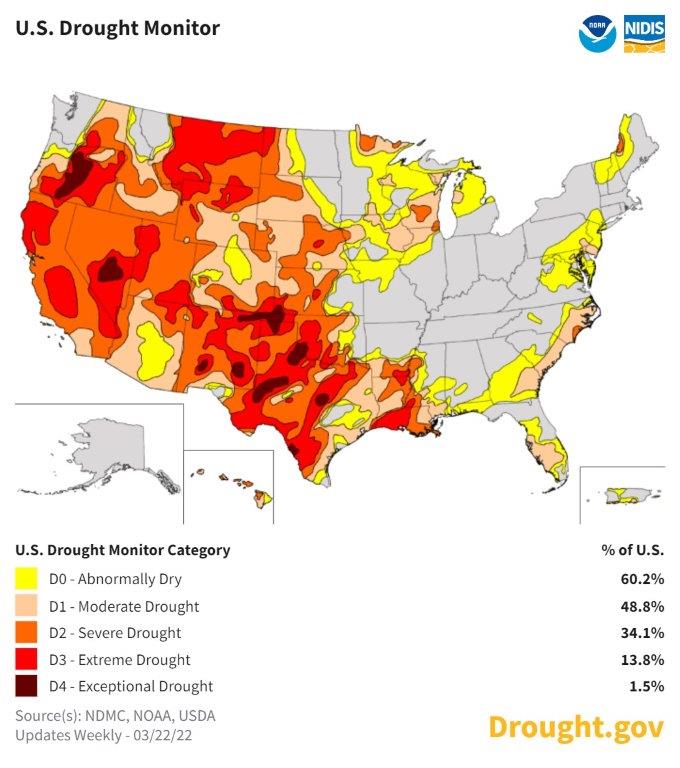

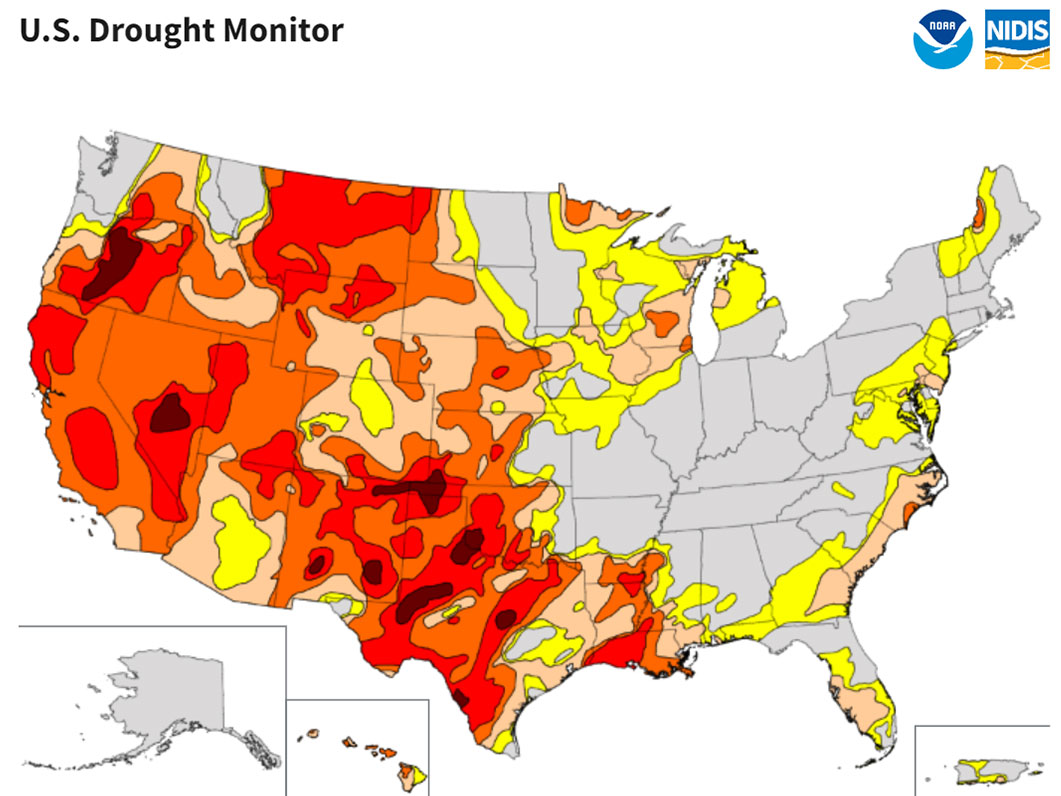

Noting that the ongoing drought “covers 74 percent of the Pacific Northwest and nearly 20 percent is in extreme or exceptional drought,” the story also said that an “unusual ridge of high pressure off the U.S. West Coast scuttled storms in January and February that the region normally counts on to replenish water levels and build up a snowpack that feeds streams and rivers in later months.”

Oregon State Climatologist Larry O’Neill said, “This year we’re doing quite a bit worse than we were last year at this time, so one of the points is to make everyone aware that we’re going into some tough times in Oregon this summer. Right now, we’re very worried about this region, about the adversity of impacts we’re going to experience this year.”

The story said that “predictions are in line with dire warnings about climate change-induced drought and extreme heat across the American West,” with “a worst-case climate change scenario playing out in real time,” according to a time study in February.

“The study calculated that 42 percent of this megadrought can be attributed to human-caused climate change,” the story said.

“Climate change may be changing [the] storm track, but there is yet no consensus on how it is affecting the Pacific Northwest,” O’Neill said.

The National Interagency Fire Center earlier in the year designated all of central Oregon as “above normal” for fire danger starting in May, which the story said is “one of the earliest starts of fire season in the state ever.”

The U.S. Drought Monitor reported that “most of central and eastern Oregon is in exceptional or extreme drought,” and it said that “parts of eastern Washington and western and southern Idaho are in severe drought.”

The story said that seven counties in central Oregon are experiencing the driest two-year period “since the start of record-keeping 127 years ago,” and “overall Oregon is experiencing its third-driest two-year period since 1895, the experts said.”

Many reservoirs in Oregon are anywhere from 10 percent to 30 percent lower than YTD 2021, “and some are at historic lows, signaling serious problems for irrigators who rely on them to water their crops.”

David Hoekema of the Idaho Department of Water Resources said that

Southern Idaho is also experiencing severe drought and a major reservoir in the Boise Basin has below average water supply, and he commented, “It takes more than just an average year to recover and it doesn’t appear that we’re going to have an average year,” he said. “At this point, we expect southern Idaho to continue in drought … and we could also see drought intensify.”

Some of the state’s driest areas have already run into trouble, with the Klamath Basin seeing domestic wells run dry.

“Ivan Gall, field services division administrator for the Oregon Water Resources Department, said that state water monitors have measured a troubling drop in the underground aquifer that “wasn’t replenished by winter precipitation,” the story said.

Between Jan. 1 and March 4, Gall’s agency received 16 reports of domestic wells that had run dry “and is scrambling to figure out how many more wells might go dry this summer in a cascading crisis.”

Farming season in the agricultural powerhouse began in early March, and the story said that during summer 2021 “farmers and ranchers in the basin didn’t receive any water from a massive federally owned irrigation project because of drought conditions and “irrigators instead pumped much more water than usual from the underground aquifer to stay afloat.”

The Oregon piece of the story concluded, “The tension over water gained national attention when, for a brief period, anti-government activists camped out at the irrigation canal and threatened to open the water valves in violation of federal law.”

Gall said, “We’re going to start this year’s pumping season 10 feet lower than we did last season, which is a problem. I think it’s going to be another rough water year in the Klamath Basin.”

Follow the US Drought Monitor at https://www.drought.gov/