In early August 2015 OnionBusiness.com took a long look at the strong El Niño that was predicted for the Sierra in California. Would it ease the state’s devastating drought? Would it even materialize?

At the time the National Weather Service said winter 2015-16 had a 95 percent chance of seeing a strong El Niño – and there was even better than a 60 percent chance it would be the strongest on record. But even then, experts were cautioning that it would and will take more than one winter’s worth of precip to bring lakes and reservoirs back to normal capacity.

That said, how did the weather pattern stack up? Several sources have reported El Niño was indeed the strongest on record, but although the Sierra did receive rain and snow, much, much more is needed.

In a June 10 piece entitled “El Niño is dead. Long live La Niña!” correspondent Doyle Rice wrote on usatoday.com that after 17 months, El Niño had succumbed to natural causes.

Rice wrote, “Developing from a small patch of warm water in the Pacific Ocean, this El Niño grew to among the largest ever recorded as it shaped weather around the world. In the U.S., it delivered much-needed rain and snow to parched California, but failed to end the state’s historic five-year-old drought.”

Rice also said that as the warmer-than-average Pacific Ocean water cools, it produces El Niño’s “kid sister, La Niña.”

So now meteorological attention is focused on La Niña, which is the cooler opposite of El Niño and which can produce a very active Atlantic hurricane season, according to the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration. Rice cited reports that “La Niña will likely form as early as late summer” and could remain active through the fall and winter.

So now meteorological attention is focused on La Niña, which is the cooler opposite of El Niño and which can produce a very active Atlantic hurricane season, according to the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration. Rice cited reports that “La Niña will likely form as early as late summer” and could remain active through the fall and winter.

Meteorologist Kelly Reardon at cleveland.com further explained the weather systems in a June 17 blog: “El Niño and La Niña are two of the three phases of a natural cycle called ENSO – the El Niño/Southern Oscillation – across the tropical Pacific. ENSO oscillates between El Niño conditions, neutral conditions, and La Niña conditions.”

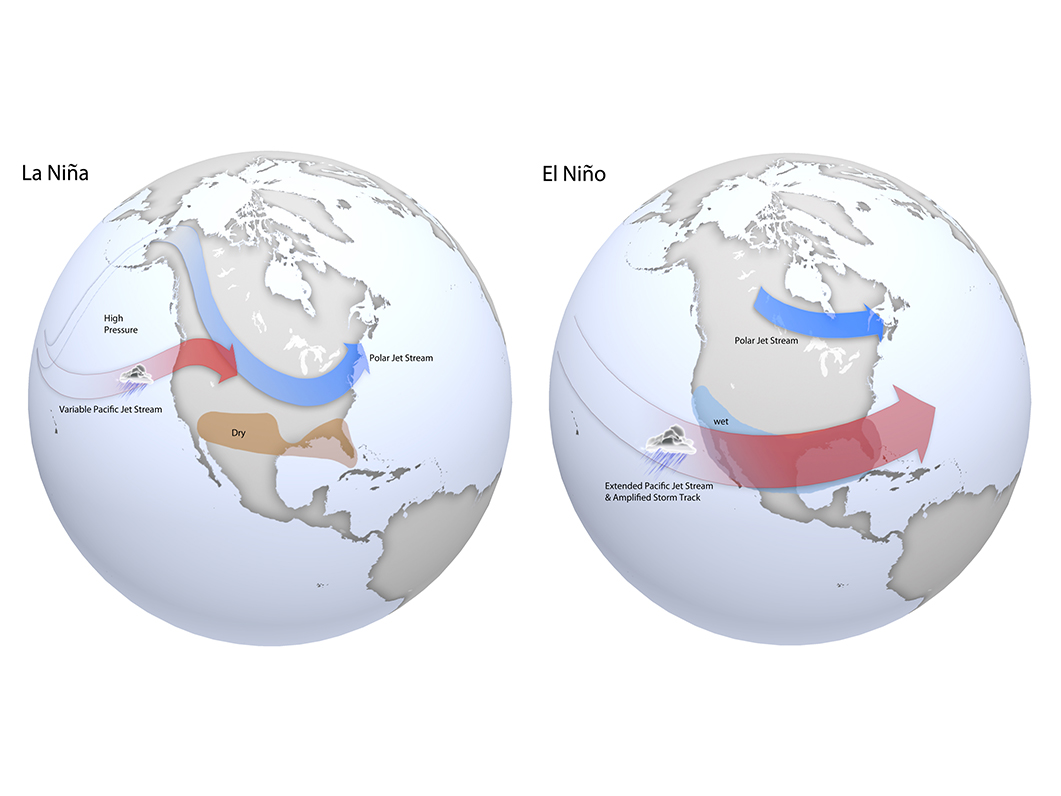

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration explains that each full ENSO cycle lasts three to seven years. Within the cycles, weather patterns are irregular. “La Niña generally follows El Niño with neutral conditions in between, but there are no guarantees,” Reardon wrote. “The two phases have a global effect on both temperature and moisture conditions…” and “… during El Niño, the southern portion of the United States sees wetter than normal conditions, but most of the country sees either neutral or drier than normal conditions.”

She wrote, “The effects of El Nino are strongest in the winter, and cause different weather conditions across the United States.”

Conversely, “La Nina causes sinking motion in the Pacific, and rising motion in the Atlantic,” Reardon wrote. “Strengthening winds across the Pacific push the warm surface water away, bringing up cooler water below. This cooler water initiates sinking motion in the atmosphere over the Pacific, which dries things out.

The cool water can also shift the position of the jet stream, shifting the threat for severe weather north. The Pacific Northwest is colder and the southeastern portion of the United States is warmer than average. As for moisture, wetter than normal or neutral conditions are expected across most of the country in the north, and drier conditions in the south.”

La Niña conditions can last nine months to a year and is strongest during the winter.

Thomas Sumner reported at https://student.societyforscience.org/article/last-year’s-strong-el-niño-gone-next-la-niña in late June that “… NOAA now estimates that there is a 75 percent chance that La Niña will take over in the coming months. La Niña can cause droughts in South America and heavy rainfall in Southeast Asia. It also can make hurricane seasons in the Atlantic Ocean more intense.”

His parting words? “Stay tuned.”